Since early 2016, I’ve been following the trends of what is likely an actual conflict in development. We can’t exactly call it a cold war because it does feature routine but low-level violence. It’s really a low level civil conflict born out of a very hot culture war.

This isn’t the first time elements of American society have engaged in a civil conflict. The period from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s had similar types of political violence and civil unrest. The structural fault lines of this period were racial and economic, with the primary accelerators centered around competing movements fighting over institutional discrimination, racism and segregation, inequality, and the anti-war movement. The most prominent trigger occurred in 1968, with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., which spurred weeks of race riots across the country. The end result: 43 Americans were killed; 3,500 were injured; and 27,000 were arrested. Damage caused by fires and riots was estimated to have been in the millions of dollars (in those days’ costs). That wasn’t the end of social turmoil or conflict, but I use this as an example of what could happen again.

Today’s structural fault lines continue to be primarily racial, ideological, and economic, stoked by accelerators that include undeniable media propaganda, a toxic political climate that clearly defines belligerents, and what will eventually be deteriorating economic conditions. A trigger could be a high profile case of violence, such as a murder, assassination, or some other heinous crime; a political event that threatens some aspect of state legitimacy (i.e., impeachment); or a disruption of critical infrastructure that tips otherwise civil society into friction.

All these are distinct possibilities, but this isn’t to say that we’ll experience one trigger like April 1968. And triggers can be impossible to predict with any certainty. One month prior to the self-immolation of Mohammad Bouazizi — the man who literally sparked the Arab Spring — there was another case of self-immolation in Tunisia that didn’t trigger the Arab Spring. It’s widely recognized that the Central Intelligence Agency failed to warn of imminent unrest after both of those potential triggers. Regardless of when or if a trigger event will occur, I continue to believe that we’re in what’s called “low intensity conflict” due to the current structural fault lines, which are likely to persist or worsen.

A low intensity conflict is a war in the gray area below the threshold of conventional war but above routine, peaceful competition. The political warfare that’s plagued the country since its founding is routine, peaceful competition. When we talk about a civil war or a domestic conflict in America, what we’re really discussing is a very small fraction of society. We can look at small wars and insurgencies throughout history — especially sectarian and ethnic conflicts that don’t involve conventional forces — and see that anywhere from one to five percent of the population at war is the norm. Beyond that, there’s 10-25 percent who favor either one side or the other, and the majority of people really are just trying to live their lives and ensure better futures for their children.

Beyond just political and cultural warfare, we’re definitely seeing the development of economic warfare, a sign of escalation in the culture war. This is economic dislocation, especially by the Left, through online publishing of personal information (“doxxing”), coordinated campaigns to have members of opposing groups fired from their jobs, and campaigns to have individuals and organizations de-platformed from social media and other online services (like PayPal, Patreon, and crowdfunding websites).

These primarily non-violent tactics will continue to be the case, however, now that economists and financial analysts are starting to talk about a recession, we should seriously consider how these groups will respond to worsening economic conditions in the next few years. High youth unemployment is a universal early warning indicator of social unrest; it’s what accelerated the Arab Spring. The youth (generally referring to ages 15-30) also happen to be the most susceptible to Far Right or Far Left ideologies. Any society with high numbers of unemployed youths who feel economic and financial despair, and who can rationalize an enemy responsible for their lack of success, runs the risk of internal conflict.

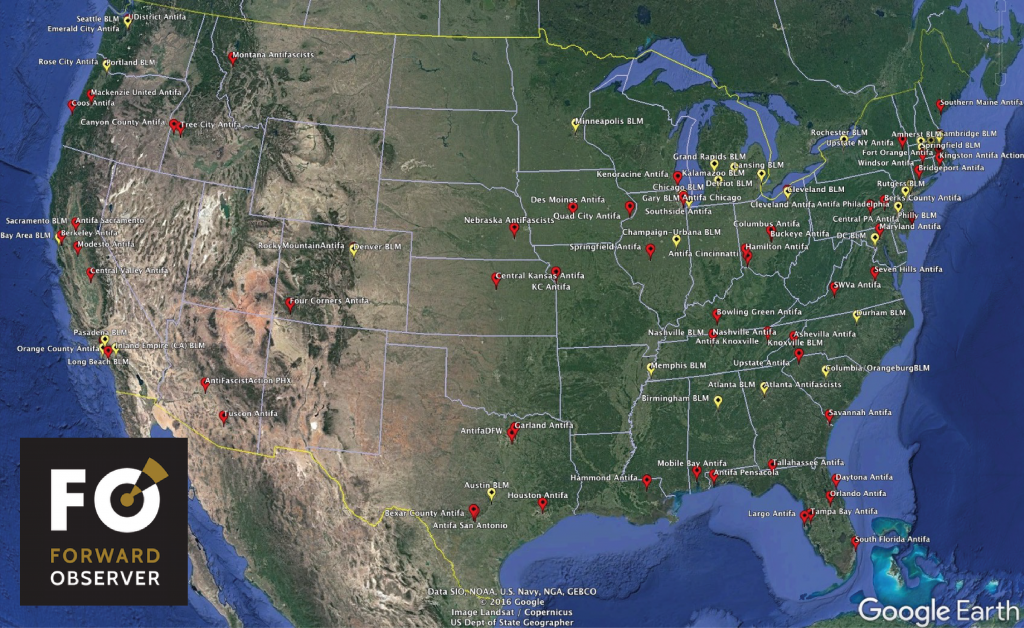

Look at most of the extremist groups today and you’ll find that they’re predominantly white and predominately below 40 on both sides, although they have older ideological forebears. (There are Black and Hispanic extremist groups, too, although they don’t have quite the national distribution that other groups have. They tend to be smaller and more geographically disparate.)

I’m still compiling my thoughts on how the next couple years could pan out, but most recently I’ve been thinking about the effects of a “lost decade” scenario marked by high unemployment and stagnant economic growth that leaves many young people with few economic options. With a lack of economic opportunity, both right wing and left wing extremism could become more appealing, as has been experienced with Islamic extremism in the Middle East. The growth of these movements could lead to greater organization, capabilities, and activities. With larger and more active groups, we would run the risk of reactionary behavior which could lead to routine violence.

This is one of several potential scenarios, but it appears that our conflict is likely to be accelerated by what happens during the next financial crisis and recession. We might have a year before that happens, maybe two or three if we’re lucky.

Always Out Front,

Samuel Culper

P.S. – These tectonic shifts in culture and politics are leading to an earthquake. You can maintain visibility on these structural risks, accelerators, and triggers of instability and violence through our Intelligence service. Try us out here to get smart on what’s straight ahead.

1 Comment